I am not entirely sure what has happened to hiring that the process has become so complicated, but I suspect it is something like “we have hundreds of applicants and they all have the same resume that they wrote with ChatGPT, so we don’t have any way to discern between candidates.”

As a result, hiring orgs have implemented novel things to try to weed out candidates who don’t make the cut on a technical level. In the past for technical roles this has taken the form of take-home assignments. I have done a couple of these and gotten offers after the fact. One was to write an essay about a GRC-ish topic, and the other one was to create a network architecture diagram that was reasonably basic. Each of these took me about 90 minutes – 2 hours, which I felt like was a reasonable amount of time to ask a candidate to spend on a take-home.

Recently, I suspect with the advent of GenAI, we have seen the rise of the “live coding assignment.” I was approached by a really solid org to take an enterprise security engineering role, and was told that I would indeed be encountering a live coding assignment, and that it would be OK as long as I knew how to code APIs, which is something I do know how to do reasonably well. I was not really sure what to expect in said assignment other than the API thing, and that my python is…competent.

Spoiler alert: I did not get the job.

I appreciate that they did not give me a bullshit task (it wasn’t “fizz buzz”, and I know how to solve “fizz buzz,” and it is the most bullshit of bullshit tasks), and they asked me to just get some data out of an API and format it in such a way that it could be piped to a SIEM.

I did make a reasonable amount of progress, and it was the kind of thing that I could’ve crushed at a take-home in two hours, but 40 minutes was just not enough time for me to deliver, and nerves probably got the best of me. As much as I find it distasteful that an org would disqualify an experienced candidate without a software engineering background by evaluating their ability to engineer software, this is unfortunately the world we live in now, so let me (the not software engineer) provide some tips on how to solve this kind of thing and what I would’ve done differently.

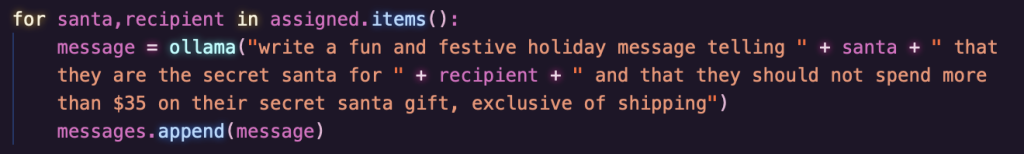

Practice in the Tool First

When I work in an API I like to have a copy of the output in front of me in an easily readable way before trying to sort out whatever field or key value pair I’m trying to get. Look, I’m in my late 30s and I like things that are easy to read.

I killed a bunch of time in this interview trying to pretty print the data to the console, only to find out that the console just would not display the pretty printed output. They had offered me access to the tool (it was Coderpad) ahead of time with a sandbox, and aside from making sure I could import the requests library (which worked), I didn’t mess around with it. I tried pasting some other working code into the sandbox after the fact that did pretty print locally, and I still couldn’t get Coderpad to play ball.

So, practice in the actual tool. If a sandbox is not offered, ask for one. If one is not available at all, maybe run away?

The Docs are the Source of Truth

Read the API docs. They are the source of truth. Almost every API has example output and input. I have never worked with an API in security engineering that wasn’t accessible with a URL and returned its data in JSON. Usually the data is returned as a list, or a dict, or a list of dicts. This API was just returning a dict, so it was reasonably easy to extract the values from the keys. For a list of dicts, it is a little more complicated, but it’s not bad as long as you understand how lists work.

Anyway, the API docs will tell you how to build your headers. Just follow them. If you are spending time thinking about doing it a different way because you know that way works, you are wasting time. Just read the docs.

Write Good Code

This is a part where the interviewer said I was doing a good job. You should know the fundamentals of how to write code. I don’t think at all that you need to be a coding expert to be good at cybersecurity, but you do need to know the basics. If you are writing everything as one big main function, your code is going to be impossible to maintain.

I originally learned to code in Java so this was basically beaten into me. Small pieces loosely joined. Small batches.

Also, do leave comments for where you think you might want to make improvements or add features. I have a bad habit of leaving comments after I am done coding rather than while I am coding, so I left a few on my live task, but it was pretty half-assed.

Talk about what you’re doing

I did not do this and should’ve. It was a stream of consciousness, but it was like, nonsensical. Essentially I was just thinking out loud and probably embarrassed myself. In fact, the interviewer probably got off the call with me and was like “this guy is insane, we can’t hire him.” I didn’t have any strategy and wasn’t intentional about talking through what I was doing. I think this cost me.

Which, after the fact, is like, “duh” right? I would’ve practiced a presentation before I gave it, why didn’t I do this here? I know how to work with an API and have done some pretty cool things with the Okta API (the one I use the most often) because Okta is terrible about letting you do operations in bulk in the GUI.

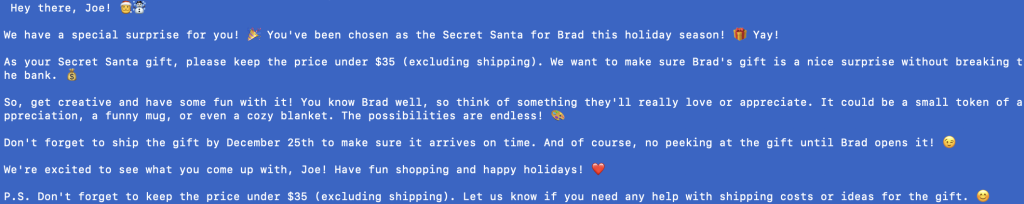

Find a way to practice/free API resources

This came down to some weird timing for me, but I should’ve found/made more time to practice before going into the interview so I had more confidence. At that point I had just gotten back from a week’s vacation and catching up on work the following week, so I didn’t do any coding and by then it had been several weeks since I coded anything at all. I didn’t make good use of the time, and just ended up constantly referencing a bunch of API code I had already written either for work or academic projects instead of having confidence in what I was doing.

”But how do I practice on an API without paying $100,000 for a SaaS tool?”

APIs are great because they can teach you about coding and give you a fun little project that you can see the results immediately, and there are tons of great APIs that are totally free!

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority API: https://developer.wmata.com – this one is fun because it presents a lot of information as a list of dicts.

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority API: https://www.mbta.com/developers/v3-api

Bureau of Labor Statistics API, which I have used for academic work: https://www.bls.gov/bls/api_features.htm

This list from GitHub on free APIs – a lot of these are kinda more “just for fun,” so if you want to know how many minutes until the next Orange Line train leaves Clarendon, it’s not for you:

https://github.com/public-apis/public-apis

Better luck next time

Considering I had never done a live coding exercise before, I feel like I did okay. I definitely did not implode, but I didn’t excel and my result didn’t deliver everything someone experienced would be able to do in the time allotted. I was disappointed, but not entirely surprised, when I heard I was not moving forward.

I didn’t make it and I own that, and it was helpful for me to have the interviewer acknowledge that, no, this is not really how we work in real life. But I’ll be reflecting on this for next time (and there will be a next time) and hope these tips are helpful. For better and worse, this now appears to be the norm in technical interviews.